![]()

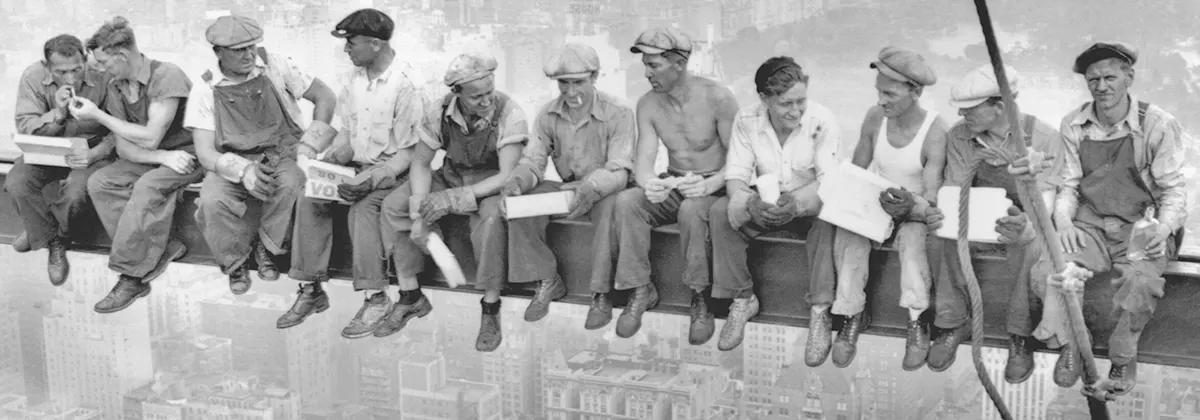

The iconic photograph known as “Lunch Atop a Skyscraper” captures a moment frozen in time, taken on September 20, 1932.

In this black-and-white image, eleven intrepid ironworkers find themselves seated upon a steel beam, soaring 850 feet (260 meters) above the bustling streets of Manhattan, New York City.

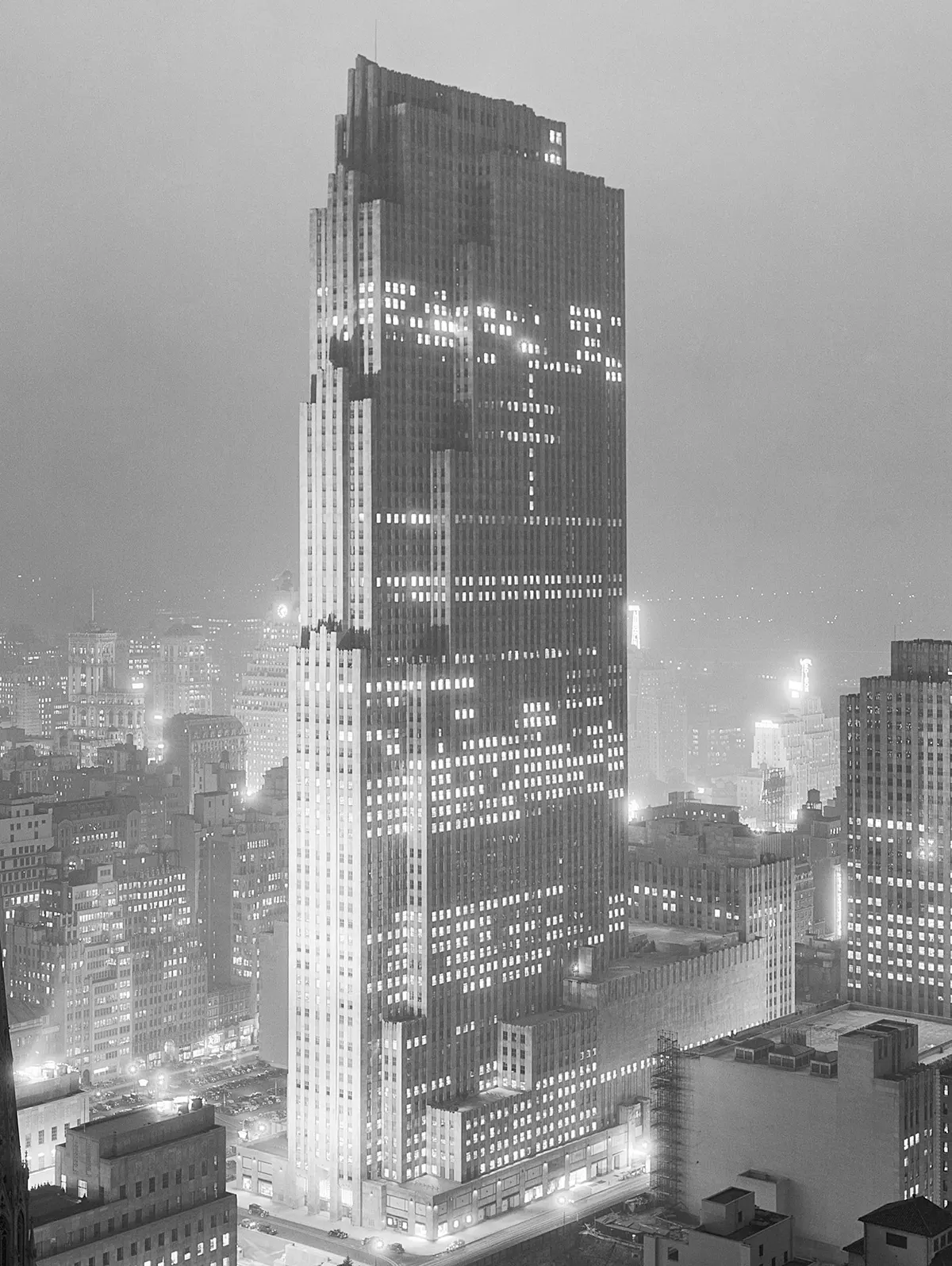

Their lofty perch is the sixty-ninth floor of what was then the RCA Building, now recognized as 30 Rockefeller Plaza, nestled within the grandeur of Rockefeller Center.

This captivating snapshot, a feat of both engineering and audacity, was arranged as a publicity stunt, part of a campaign promoting the skyscraper.

The image captures not only the grandeur of the city below but the camaraderie of these immigrant ironworkers who, despite the precipitous elevation, partake in their lunchtime ritual with an air of nonchalance.

Perched in a seemingly gravity-defying manner, these men, who often navigated the complex network of girders with casual familiarity, etched a unique chapter in the city’s history.

The RCA Building in December 1933 during the construction of Rockefeller Center.

The Identity of the Ironworkers

According to a New York Post survey, numerous claims have been made regarding the identities of the men in the image.

The 2012 documentary Men at Lunch investigated claims that two of the men were Irish immigrants, and the director reported in 2013 that he planned to follow up on other claims from Swedish relatives.

The film confirms the identities of two men: Joseph Eckner, third from the left, and Joe Curtis, third from the right, by cross-referencing with other pictures taken the same day, in which they were named at the time.

The first man from the right, holding a bottle, has been identified as Slovak worker Gustáv (Gusti) Popovič.

The photograph was found in his estate, with the note “Don’t you worry, my dear Mariška, as you can see I’m still with bottle” written on the back.

The third worker (from the left) has been identified as Joseph Eckner; Joe Curtis, third from the right. The last one (on the right) is Gustáv (Gusti) Popovič. The rest remain unknown.

The photograph has been referred to as the “most famous picture of a lunch break in New York history” by Ashley Cross, a correspondent of the New York Post. It has been used and imitated in many artworks.

Although critics have dismissed the photograph as a publicity stunt, Johnston called it “a piece of American history”.

Taken during the Great Depression, the photograph beca me an icon of New York City and has often been re-created by construction workers. Time included the image in its 2016 list of the 100 most influential images.

Discussing the significance of the image in 2012, Ken Johnston, manager of the historic collections of Corbis, said: There’s the incongruity between the action – lunch – and the place – 800 feet in the air – and that these guys are so casual about it.

It’s visceral: I’ve had people tell me they have trouble looking at it out of fear of heights. And these men – you feel you get a very strong sense of their characters through their expressions, clothes, and poses.

The “Lunch Atop A Skyscraper” Picture’s Photographer is Still a bit of a Mystery

Charles Clyde Ebbets.

The identity of the photographer is unknown. It was often misattributed to Lewis Hine, a Works Progress Administration photographer, from the mistaken assumption that the structure is the Empire State Building.

In 1998, Tami Ebbets Hahn, a resident of Wilmington, North Carolina, noticed a poster of the image and speculated that it was one of her father’s (Charles C. Ebbets; 1905–1978) photographs. In 2003, she contacted Ken Johnston of Corbis.

Corbis, a company that provides archived images to professional photographers, hired Marksmen Inc., a private investigation firm, to find the photographer. An investigator discovered an article from The Washington Post, which credited the image to Hamilton Wright.

The Wright family, however, was not familiar with the photograph. It was common for Wright to receive credit for photographs taken by those working for him; Hahn’s father had worked for the Hamilton Wright Features syndicate.

Charles C. Ebbets with his trusty camera hanging out over New York City.

In 1932, Ebbets had been appointed the photographic director of Rockefeller Center, responsible for publicizing the new skyscraper.

Hahn found her father’s paycheck of $1.50 per hour (equivalent to $32 per hour in 2022), the ironworkers photograph, and an image of her father with a camera, which appeared to be of the same place and time.

Analyzing the evidence, Johnston said: “As far as I’m concerned, he’s the photographer.” Corbis later acknowledged Ebbets’s authorship.

It was later discovered that photographers Thomas Kelley, William Leftwich, and Ebbets were present there on that day. Due to the uncertain identity of the photographer, the image is again without credit.

Tee time. Photo by Charles Ebbets.

Ebbets was a daredevil himself, and his biography tells of his earlier stints working as a stuntman in Hollywood, as well as an actor in the mid-1920s, playing the role of an African hunter known as “Wally Renny” in several motion pictures. He also had many other jobs including pilot, “wing-walker”, auto racer, wrestler, and hunter.

Explore snapshots from Ebbets’ diverse journey through life on a website curated by his daughter.

With heartfelt dedication, she has carefully preserved and revived his extensive photo collection, allowing us to witness the many facets of his achievements.

Charles Ebbets at Rockefeller Center, 1932.

Portrait of Charles C. Ebbets atop a skyscraper in NYC.

Laurel and Hardy. Photo by Charles Ebbets.

(Photo credit: Wikimedia Commons / Library of Congress).